It’s never too early to begin learning a language, it’s fun, it promotes healthy development, and the many cognitive and social benefits will last a lifetime. Although, opinions are mixed when it comes to raising bilingual kids. Some parents believe that exposing their children to two (or more) languages while growing up will bring more harm than good. For instance, there is a concern that such children may mix up the languages in their heads, and will thus be late talkers or somehow acquire poor communication skills. However, much cognitive research contradicts this idea and has proven that learning a second language actually puts your child at a significant advantage.

Ondine Ullman, Head of Language Acquisition for the primary school at Bangkok Patana School says, “A language such as English can be acquired and used successfully by bi, tri and even quad-lingual students – as long as parents are aware of and make a plan for the levels of fluency or proficiency they wish to instil in their child.”

With over a decade of experience working with English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners, training EAL teachers and designing EAL learning programmes, she advises that children who learn another language before age five are uninhibited by the fear of making mistakes. Learning a second language also boosts students problem-solving, critical-thinking, and listening skills, in addition to improving memory, concentration, and the ability to multitask. Children who are exposed early to other languages definitely show signs of better mental flexibility and a more positive attitude to the cultures associated with those languages.

Make a Plan

The first step is to adopt a long-term language strategy. “Ask yourself where you see your child as a young adult – how does that fits into their language acquisition needs? Do you want them to have some literacy, be more fluent in speaking [as opposed to reading and writing] and able to use the language on a daily basis? Or do you want them to be able to speak, read and write at a tertiary level?” Ondine says. “But choose what is right for your family. We all have our own circumstances and what’s best for one family might not be best for another.”

Professor Jim Cummins, a leading global authority on bilingual education and second language acquisition, makes the distinction between two differing kinds of language proficiency: 1. Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BISC), the ‘surface’ skills of listening and speaking, which are typically acquired quickly by many EAL students, particularly those from language backgrounds similar to English who spend much of their school time interacting with native speakers; and 2. Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP), the basis for a children’s ability to cope with the academic demands placed upon them in various subjects. He states that while many children develop native speaker fluency (i.e. BICS) within two years of immersion in the target language, it takes between 5 to 7 years for a child to be working on an academic level with native speakers.

One person-One Language

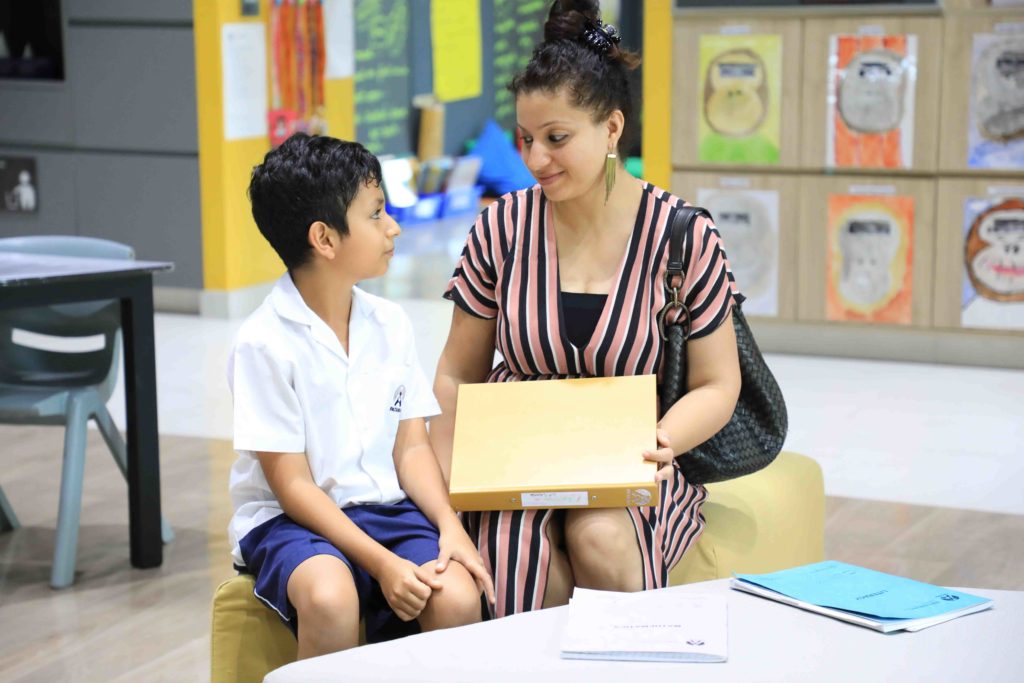

For multicultural families, Ondine explains that an ideal, and arguably the most widespread method of nurturing simultaneous bilingual development, is the ‘one person-one language’ approach where each parent speaks his or her own native language to the child. In the case where the children are in international school and studying primarily in English, but the parents are non-native English speakers, both parents should use their native language or languages at home. “If English is not the home language with complete competency, kids will be impacted and they pick up ingrained errors in language usage. Foster a strong home language, which gives children a firm foundation from which other languages can be acquired in other settings, such as school.”

In this regard, Professor Cummins explains that in the course of learning one language, a child acquires a set of skills and implicit metalinguistic knowledge that can be drawn upon when working in another language. This common underlying proficiency provides the base for the development of both the first language and the second language. Any subsequent expansion of the proficiency that takes place in one language will have a beneficial effect on the other language or languages. This theory also explains why it becomes easier to learn additional languages when the home language is mastered.

Tips For Parents

When parents ask about the best ways they can help their child at home, Ondine says that the child should have the opportunity to converse extensively in their native language in a fair amount of detail – the earlier, the better. For example, when chatting about what the kids have done in school that day, talk about the specific science experiment they did, stories they read, new concepts in maths they learned, etc.

Also, make the distinction between language fluency and accuracy. In the process of learning the home language, children will make mistakes. “Encourage mistakes but don’t jump on errors straight away.” Use corrective modelling, she says, which involves subtle corrections of a child’s spoken errors such as relaying their utterance in the correct way. Such feedback often leads to the child repeating his or her sentence correctly or with fewer errors in imitation of the parent’s model.

Another important issue in bilingual education is related to the fact that language and culture are intertwined – but the latter is often overlooked. Professor Cummins draws the distinction between additive bilingualism, where the first language continues to be developed and the first culture is valued while the second language is added; and subtractive bilingualism, where the second language is added at the expense of the first language and culture.

“When looking at international schools, ask about their language policy,” suggests Ondine. “An environment of additive bilingualism supports the learning of the home language even when it is not English. For example, if kids have the opportunity to hear and speak Thai in school in both formal and informal settings, the value of Thai as their home language and culture retains validity. Learning doesn’t diminish. Only with strong foundations in a home language can true proficiency in English be achieved, especially as an academic language.”

And finally, understand that children will pick up languages at different rates. Avoid comparing them to others, as well as expecting bilingual development to happen at the same pace or reach a comparable level of competency. “Multilingualism looks different for everyone,” says Ondine. “There is rarely an equal mastery of the first, second or third languages. It’s ideal, but not realistic.”