Dyslexia is the most common learning difficulty and affects between 5 to 15% of all children, with half of all special education students in a school being dyslexic. Even though the statistics of prevalence are high, dyslexia is often ‘hidden’ and is always a subject on any parents radar.

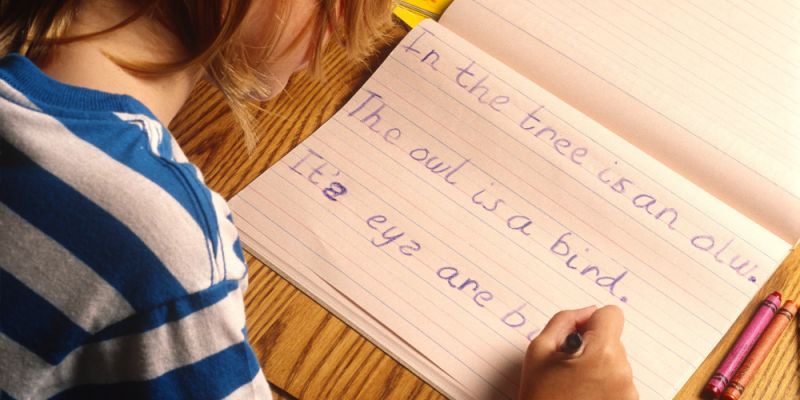

The difficulty is hidden, as children with dyslexia are often bright and demonstrate no outward sign until they learn to read. This often causes challenges for the dyslexic child, as their reading difficulties are ‘unexpected’ and are seen as having all the cognitive capability to be good readers. As a result of this perception dyslexic students are often undiagnosed, misdiagnosed or worse, labeled as ‘lazy’. Moreover, in an international school setting, the dyslexic child can often be overlooked due to issues with English as a second language and lack of appropriate assessment tools to distinguish between the two.

As the dyslexic child’s difficulties are often hidden they are not identified early enough. Without early identification and intervention before grade one, a dyslexic child has a 1 in 4 chance of reading at grade level by the end of elementary school. Whereas, the same child who receives structured, cumulative and multisensory instruction in kindergarten or grade one has a 90 to 95% chance of reading fluently by the end of elementary school (National Institute of Health, 2000). Early intervention is key to future academic success. Without early remedial intervention, the dyslexic child may develop lifelong learning blocks and a fear of learning, leading to low self-esteem and depression.

Understanding Dyslexia

The human brain is designed to naturally acquire many skills. As all parents know well, most children easily learn to walk and talk without any special instruction. But what many of us don’t realise is that the human brain was not designed to read.

Dyslexia is a neurobiological difference; recent brain imaging research shows that dyslexic children do not use the same areas of the brain when performing reading tasks as their non dyslexic counterparts, and that the areas used when reading are inefficient in processing the elements of language required. The brains ‘wiring’ to the language areas of the brain are inactive; recent Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies have given us insightful information into the origin of the dyslexic child’s difficulty to read. Moreover, research has given us insight into the types of instruction that enhance the activation in the areas required for reading. Increasing numbers of studies have shown that a structured, cumulative and multi-sensory program, such as the Orton- Gillingham language program or other interventions based on this method of instruction, can re-organise the brains neural pathways so that the language areas required for reading efficiently increase in activation.

More information on multisensory language programs for dyslexics can be found at: www.dyslexiaida.org.

Stanislas Dehaene, one of the foremost experts involved in research on reading and math in the brain, has noted that in order to read, we have to recruit brain architecture that was designed for other purposes. Fortunately, the language and visual object recognition networks of the brain mature in early pre-school years, and then multitask in a way to reconfigure it for reading.

With an alphabetic language like English, reading requires that we integrate the speech sounds of our language, the phonemes, with the letters, graphemes. This sound-letter correspondence requires the ability to perceive speech sounds quickly and accurately as well as the ability to perceive letters quickly and accurately. It is the latter skill that is contained in the visual word form area of the brain, a region at the base of the occipital lobe in the left hemisphere.

This area possesses highly sophisticated capabilities that are essential for fluent reading. For example, it lights up first when a person is asked to determine whether the words written as “READ” and “read”, are the same words. Although to most readers, that seems like a simple task, uppercase and lowercase letters such as “A” and “a” or “R” and “r” or even “D” and “d” are actually not at all alike in shape or configuration. We have to learn to “see” them as the same letter even though they are very different shapes.

For many with dyslexia, this part of the brain is not responding the way it does in typical readers and shows no specialisation for written words. Moreover, recent research indicates that dyslexics have trouble with both hearing the sounds within words and recognising letters. In other words, not only do children who struggle to read have problems perceiving the sounds within words, they also appear to have trouble recognising letters.

New Research Areas

New research points to the importance of reading interventions that improve all components of reading disorders: auditory perception, phonological awareness, language skills and visual letter recognition. It also highlights the importance of interventions that have evidence-based data revealing the underlying brain structural changes that coincide with the intervention components.

Fortunately, such discoveries in brain science are not only helping us understand these important brain regions, they are also providing research to show how specific targeted interventions, like Fast ForWord, not only improve reading skills but activate those very areas that appear essential to successful reading achievement.

With so much at stake for the unidentified dyslexic child, awareness of the early warning signs of dyslexia and the best methods of instruction are key for future academic and lifelong achievement for dyslexic learners. Dyslexia doesn’t need to hold your child back. Equipped with the right tools, a dyslexic child can go back to the mainstream education system and be extremely successful.

Read more about research about Fast For Word and dyslexia here.

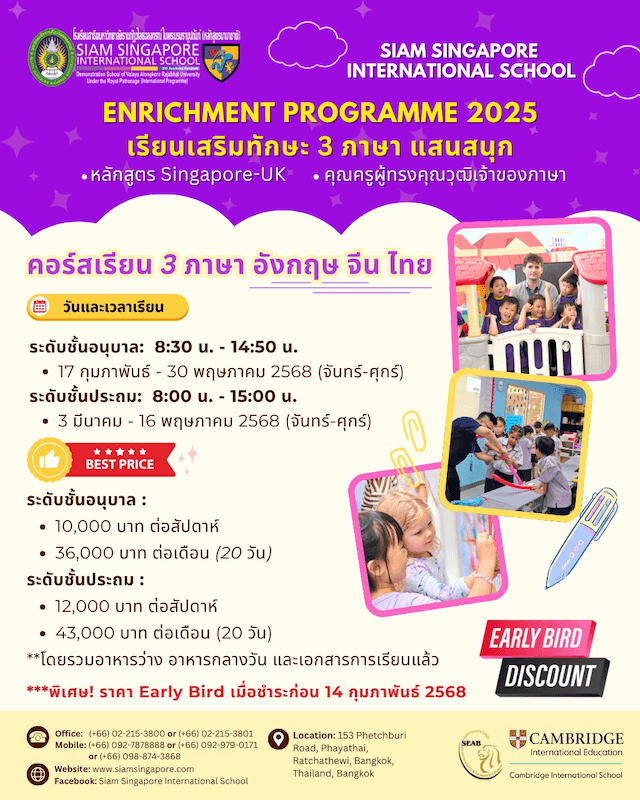

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored content by BrainFit Studio Bangkok.